How could what was crystal clear to my content-oriented brain not be clear to others?

In 2013, I was new to my marketing career yet had a taste of that valuable first job experience under my belt. That's when I repeatedly made the naive assumption that everyone else was dumb for not going all in on my latest great idea.

Turns out, I was the stupid one (duh) 🙈

Since that realization, I've experimented with different ways to package my thoughts. I turned my weakness into a strength and don't feel like a chronically misunderstood marketer scrambling all over the place.

But marketer or not, there's no point in having a wishlist of great ideas if you can't get buy-in to execute those ideas. You also don't want to be that person who people dread getting a notification from due to bad reputation of sending confusing messages and wasteful meetings.

In this post, I'm sharing what I wish I'd known as a naive, overly confident marketing newbie on the following topics:

Let's dive into why I failed and how I fixed those mistakes for each of these.

1. Pitching Ideas (Or Asking Questions)

Why I failed:

- Too short (or too long), poorly formatted messages with a weak idea structure

- Bad timing and communication of level of urgency

- Unclear desired outcome

Whether I had a great idea or an important question, there were times I would get either no answer, an incomplete answer, or an unexpected negative response.

People engage when you make it easy to engage. When it comes to pitching or asking a question, being clear on the following is a must:

- The problem and why it matters

- The solution (if pitching an idea)

- What action do you want the recipient(s) of your pitch or question to take next?

Maybe you technically did include these in your delivery be it a written update, video, or real-time conversation. But your colleagues didn't get it because the problem, solution, and desired action was hidden in a wall of text or confusing rant.

While our brains are wired to find patterns in data, it's your job to make that pattern easy to spot with the way you tell your story and visually present it.

I had a bad habit of giving excessive context which led to often disconnected ideas. This meant I had no real story. It was more like a massive laundry list of things on my mind.

Nowadays, here's what I do.

- I first decide what I want to get out of my pitch or question.

- From there, I work backwards to understand what type of story will resonate with the message recipient(s) so I can label the problem and why it needs to be addressed.

- Once that's clear, I can zoom in to the more granular details of what context is relevant to helping people see what I see so they can easily deliver an informed response.

In the next section, I'll build on this idea as I go over the visual part of presenting.

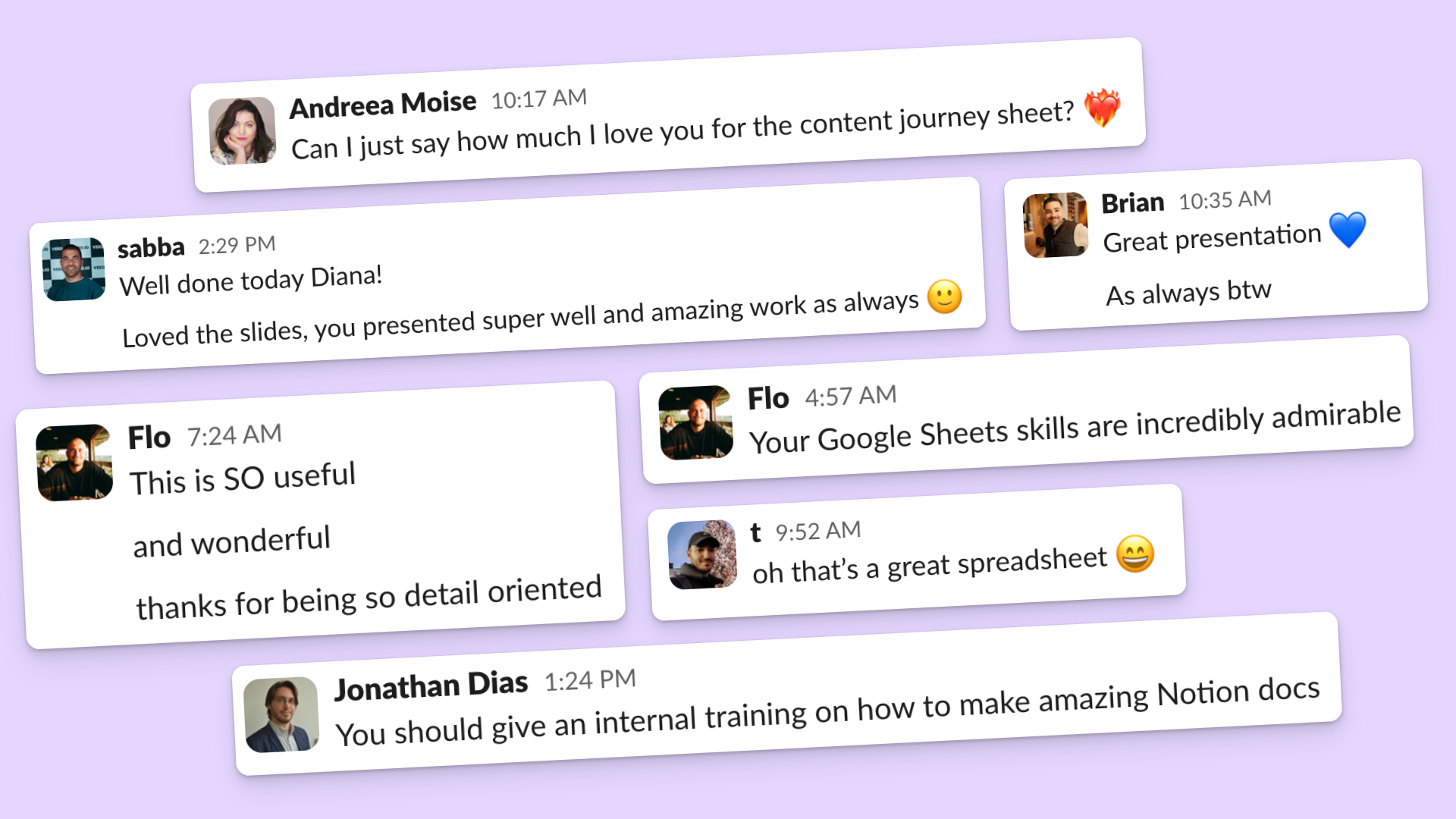

2. Building Presentation Decks

Why I failed:

- Info dumping on my slides

- Lack of supporting data

The problem isn't necessarily having too many slides. It's also not having a lack of design skills. Some of the best decks that have been presented to me were ugly but effective.

Understanding your presentation shouldn't feel like it requires painstaking focus.

Here's what happens when you try to do too much:

- You try to cram more words and visuals than a slide can handle and so you're making it hard for people to understand.

- When audience understanding is negatively affected, viewer retention dips.

- When retention dips few engage.

- Nobody engages and you're back to square one.

I like to start my presentations the way I start any other piece of content.

Ugly.

Messy.

A pile of idea diarrhea.

Version one is never pretty (and if it is you're probably wasting time).

When you dump the pieces on the page you can see everything that once only lived in your head. You can then treat it like a puzzle as you rearrange the pieces and it all comes together just right.

So rather than make a simple five to 10-slide deck from the get-go, focus on emptying your brain onto the doc.

As you organize the mess, think of it as breaking down your pitch into neatly labeled chapters kind of like how sometimes you have partially solved chunks of a puzzle before you figure out how the chunks come together to form the picture.

Like the puzzle chunks, each chapter is a new slide helping you frame your ask through your story.

If you're looking for some good reads specifically about presentation design, here are two books I found useful:

- DataStory: Explain Data and Inspire Action Through Story

- Everything I Know About Life I Learned from Powerpoint

Of course, I also highly suggest studying storytelling and copywriting but I find my most valuable lessons have come from trial and error rather than books for this part.

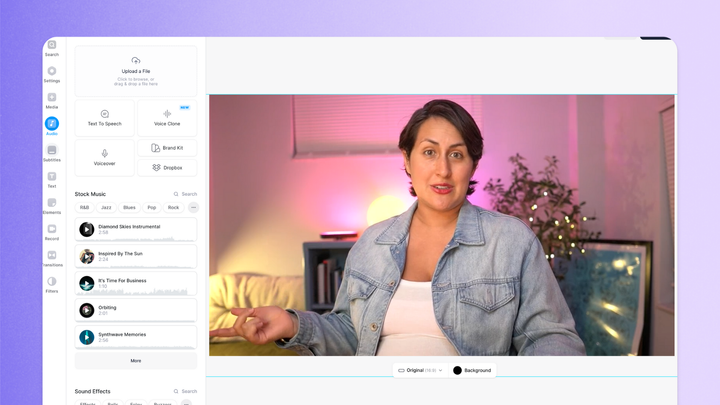

3. Showing Slack Updates of My Work

Why I failed:

- Too much what not enough why and how

At first, I was too silent and therefore nearly invisible at work. So then I tried to be more visible by sharing about my work.

I'd share a list of what was published the previous month and get little to no responses. In retrospect, from a non-marketer's POV it can be like "yeah, so what?"

Now I know I can't assume people will connect the dots and understand why my work update matters. Prefacing my actual update with some context on the problem, why it matters to the team and company as a whole, and then diving into the actual update helped me drive more interest from others in the work we were doing.

Depending on the importance of the update, how much detail you go into may vary. If you're talking about annual plans then a meatier update makes sense whereas a monthly or project update is more bite-sized.

Formatting is everything.

Here's a list of formatting options you can incorporate to make easier-to-read updates:

- Grouping related ideas in short paragraphs or sentences

- Bold, italicized, and underlined text

- Emojis (🗓️) and symbols (↳)

- Adding images or video

- White space

- Bullets

- Links

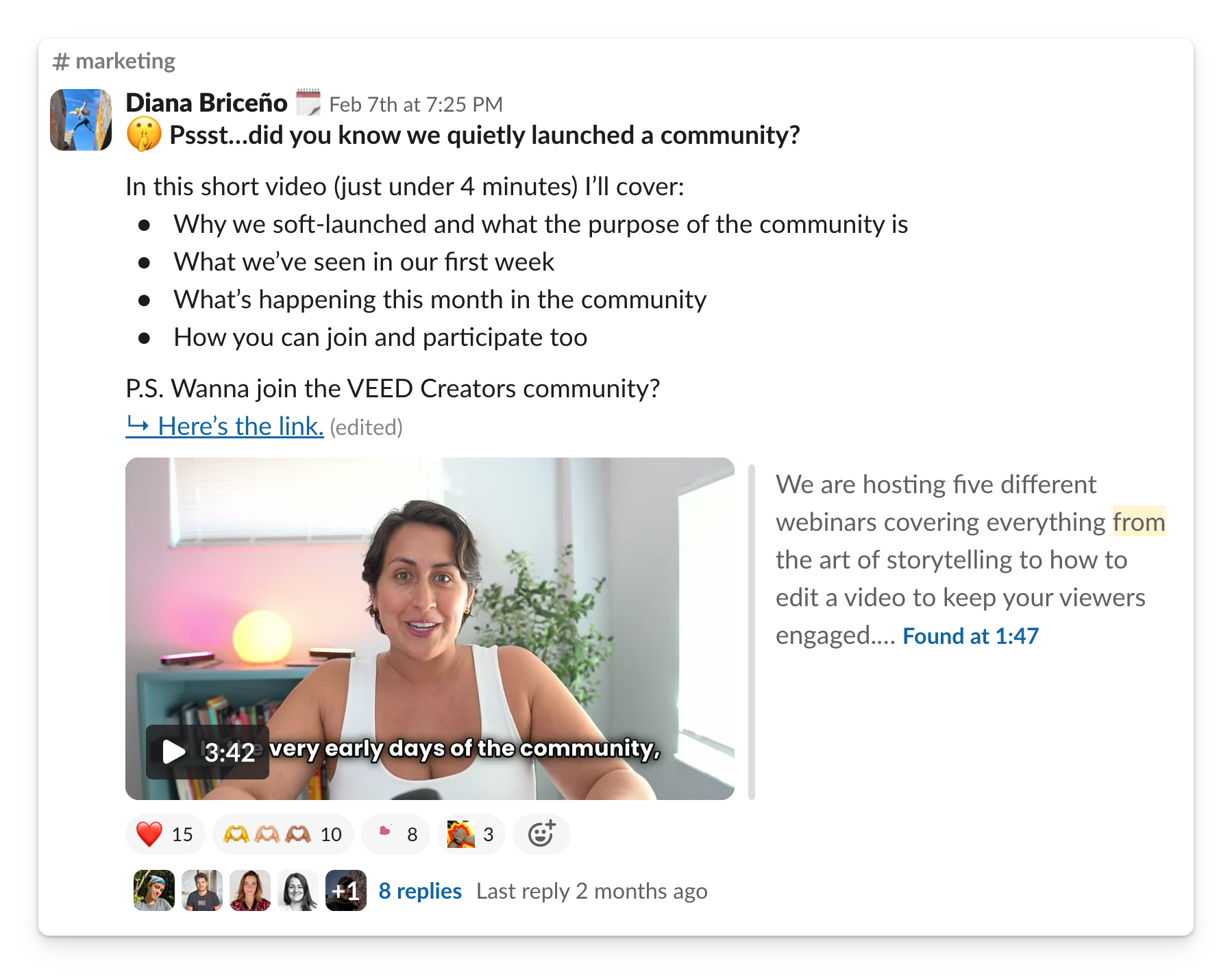

You also want to pretend you're writing for social in the sense that your update leads with a strong hook that makes people want to read. There's not that much of a difference between your noisy Slack feed VS LinkedIn feed at the end of the day.

We're all here trying to be heard.

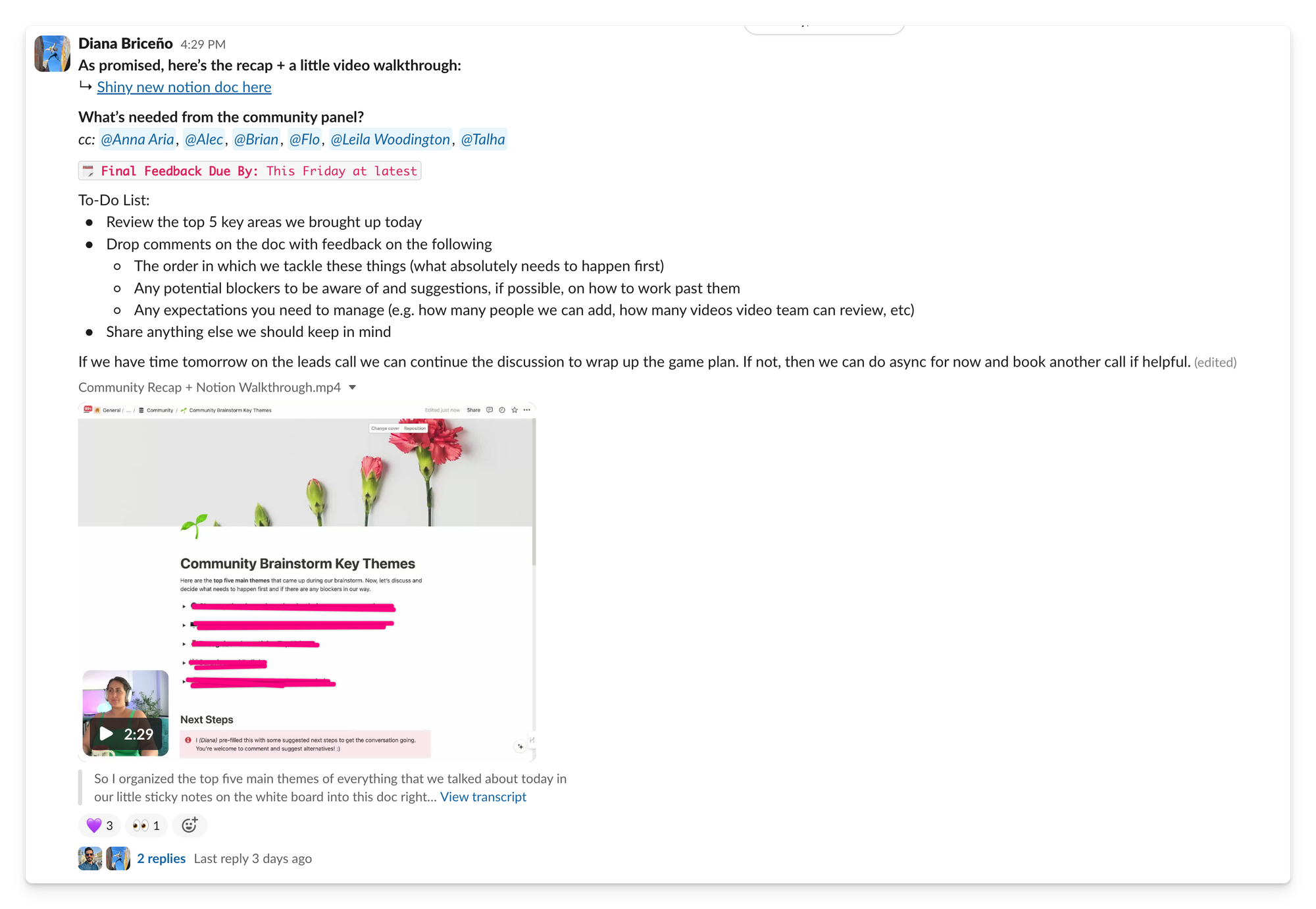

Here's an example of what this formatting could look like in action:

4. Giving Content Editing Feedback

Why I failed:

- Lacked candidness and sugarcoated things

- Pointed out what was wrong but not what great looked like

- Did not point out what was done well

"Your first draft is as good as your content brief. Your final draft's message will be as strong as your edits."

I was scared to be candid because I was scared to be perceived as mean or difficult even though my delivery was never harsh and my intentions never cruel.

As a new editor, I would sugarcoat my feedback. The feedback ended up being long-winded which did the following for me:

- Hid the actual feedback in a pile of words like a needle in a haystack

- Which led to unread feedback

- And I got back bad content

After a while, I realized there was no way I could continue on this same path without losing my mind and wasting everyone's time. Somewhere along the way, I came across the author Kim Scott who wrote Radical Candor whose book changed the way I perceived myself as a leader and the way I needed to deliver feedback.

Here's what I began to do to give better editing feedback:

📘 Context + Open-Ended Questions

Explain what good looks like to you and why you don't like something rather than just crossing something out and asking for a rewrite. Be clear about what the right direction looks like (especially if you're working with newer writers who need a bit more guidance).

And if you can, allow room for learning by asking them how they would rework the section given the new context. This not only helps the writer learn but creates a healthy collaborative environment.

📘 Examples, Examples, Examples

This kind of goes with the above but if you can describe within the text or link to something that helps explain your vision, do it. It's hard sometimes to understand what's in your head without giving the other person an example to help with visualization.

📘 Add Suggestions + Commentary

Sometimes adding rewrites yourself directly on the doc is the best way to provide context or an example of what you want. But rather than just leave a bunch of rewrites, leave comments to explain why. This helps the writer see and understand what you want in the future.

📘 Highlight The Good Stuff You Want More Of

Editing is not just about highlighting what needs to go but also what you love and want to keep seeing from the writer.

This not only makes the sometimes tough process of reading feedback feel a bit nicer but also helps the writer know your definition of what good looks like. My favorite writers keep logs of notes to remind them of the things I really love and don't love from their work.

📘 If Performance Is Dipping, Talk About It

We're all only human. Sometimes the quality dips and you're left wondering why. Should you say something? If so, when? Or should you just wait and hope the next time it's all better?

From my experience, it's better to acknowledge and talk about these things sooner rather than later when it might already be too late. Don't think of it as if you're reprimanding but rather approaching the situation with compassion and curiosity.

- Sometimes a writer is scaling their business and training new writers who are getting up to par with your work

- Sometimes a writer is going through a rough personal patch and having a tough time balancing client work with life challenges

- Sometimes it's actually the case where the writer just doesn't care and it's time to part ways

But you'll never know which of these it is unless you create the space for open and candid communication.

In the long run, the more upfront effort you invest in educating your writers (within reason) the less time you'll spend fixing up the first draft.

P.S. I wrote this blog about my content briefs if you want to read more about the briefing and outlining phase of the work.

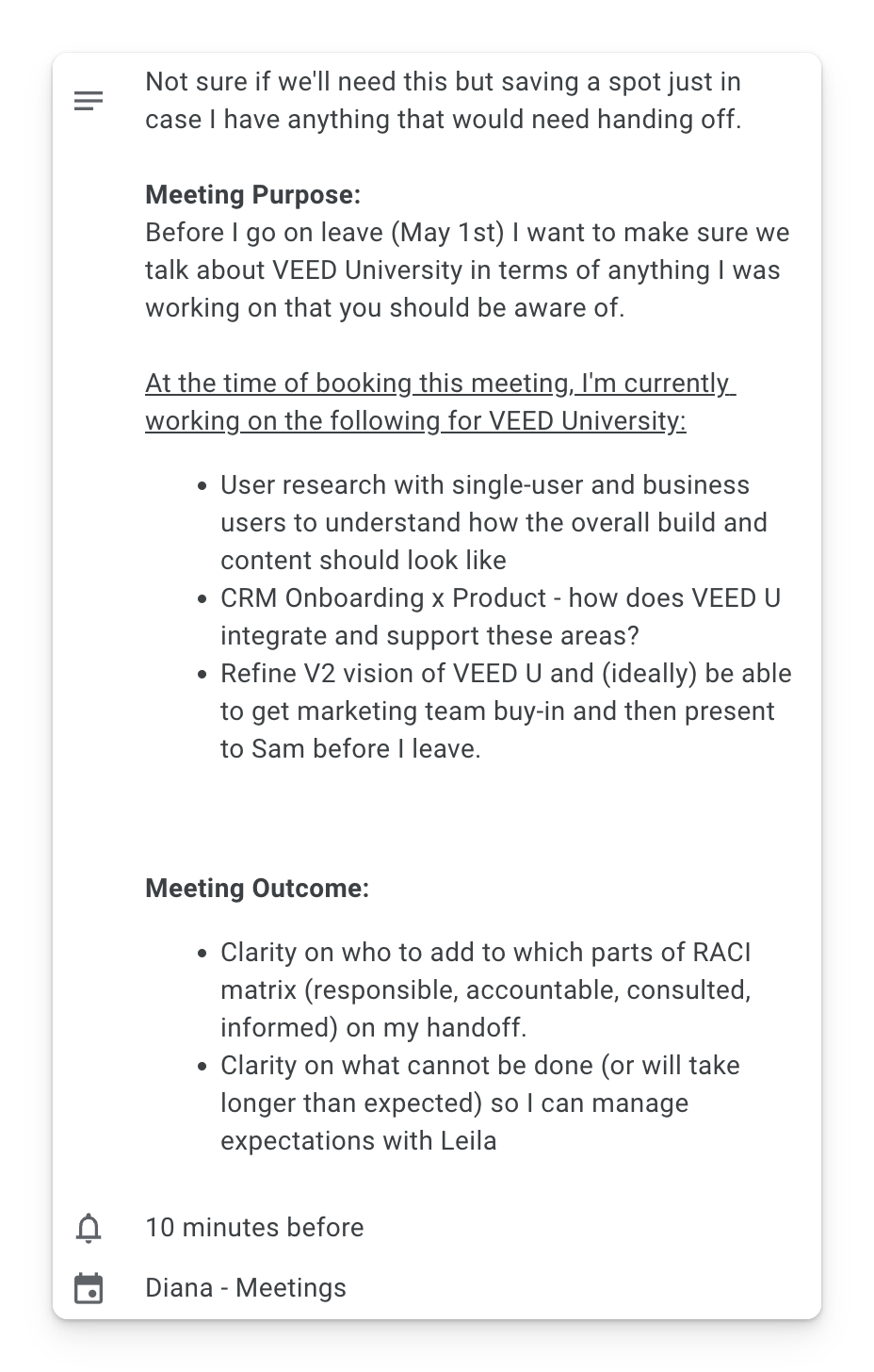

5. Booking and Running Useful Meetings

Why I failed:

- Booking time with zero context or desired outcomes

- Spending too much time worrying about what to say rather than listening

Meetings get a lot of hate and for good reason. Most meetings suck because most people suck at deciding when to host one and how to run it.

Meetings are great when...

- You know why you're in the meeting

- Everyone knows what they need to get out of it

- They're (ideally) not a last-minute event so you have time to think beforehand

I'm not sure why I'm like this but, during a brainstorming meeting with no context prior to the call, I feel like my brain glitches and only starts working again when I get off a call. I find myself more concerned about not sounding stupid and finding something, anything to say, rather than coming up with actually good ideas. I feel rushed because I didn't have time to process and let the topic of the meeting sink in.

Because of this, I tend to be mindful of others who may feel the same. So here's what I like to do which I've found keeps meetings within the agreed time frame (or even shorter).

🗓️ Decide if this is an async or real-time solution type of discussion

First off, is this a complex or time-sensitive problem or educational presentation that needs real-time discussion or is it a simple thing that can be solved via slack on a more flexible schedule?

🗓️ Collect relevant reference docs + set a meeting outline

If possible, give yourself some time in advance (ideally more than two days prior) so you give people time to consume the context notes for the call.

Gather or create relevant reference docs to help people get up to seed and jot down a simple bulleted list with two things:

- Why is this meeting taking place?

- What outcome(s) should we get out of this time together?

This helps people understand why they're there, keep the conversation flowing in the right direction, and waste less time since you can dive straight into it.

🗓️ Send a recap when relevant

The meeting is useless if you don't hold yourself and others accountable for the things you said you'd do. If you discussed the next steps of a project, send a quick recap to the group with who's doing what and the deadlines.

It helps to keep a notes document with more in-depth context when possible which you can link to in your quick recap message.

These are the main mistakes I've made. I've seen many others for which I've been on the receiving (like people who tag you in 20+ message mega-threads and ask, "thoughts?").

Maybe that's a post (or update to this piece) for another day. 😆